Hinduism in

The advent of Suharto's 'new order' resulted in an increasing Indonesianisation of both Hindu Dharma and Parisada Hindu Dharma, partly due to the fact that every Indonesian citizen was now required to be a registered member of one of the five acknowledged religious communities (Islam, Christianity [i.e. Protestantims or Catholicism], Hinduism and Buddhism). Inspired by the Hindu Javanese past, several hundred thousand Javanese converted to Hinduism in the 1960s and 1970s. When the adherents of the ethnic religions Aluk To Dolo (Sa'dan Toraja) and Kaharingan (Ngaju, Luangan) claimed official recognition of their traditions, the Ministry of Religion classified them as Hindu variants in 1968 and 1980. The Parisada Hindu Dharma changed its name to Parisada Hindu Dharma

CONTENS

- History

- General Beliefs and practices

- Hinduism in Bali

- Javanese Hinduism

- hinduism elsewhere in the archipelago

- Hindu holidays in Indonesia

- In a Political Context.

- In a Social Context

- In an Economic Context

HISTORY

At the peak of its influence in the 14th century the last and largest among Hindu Javanese empires, Majapahit, reached far across the Indonesian archipelago. This accomplishment is interpreted in modern nationalist discourses as an early historical beacon of Indonesian unity and nationhood, a nation with Java still at its center.

That the vast majority of contemporary Javanese and Indonesians are now Muslims is the outcome of a process of subsequent Islamization. Like Hinduism before it, Islam first advanced into the archipelago along powerful trade networks, gaining a firm foothold in Java with the rise of early Islamic polities along the northern coast. Hinduism finally lost its status as Java's dominant state religion during the 15th and early 16th century, as the new sultanates expanded and the great Hindu empire Majapahit collapsed. Even then, some smaller Hindu polities persisted; most notably the

Islam met with a different kind of resistance at a popular and cultural level. While the majority of Javanese did become 'Muslims', following the example of their rulers, for many among them this was a change in name only. Earlier indigenous Javanese and Hindu traditions were retained by the rural population and even within the immediate sphere of the royal courts, especially in a context of ritual practice. In this sense, the victory of Islam has remained incomplete until today.

GENERAL BELIEFS AND PRACTICES

Practitioners of Agama Hindu Dharma share many common beliefs, which include:

A belief in one supreme being called 'Ida Sanghyang Widi Wasa', 'Sang Hyang Tunggal', or 'Sang Hyang Cintya'. God Allmighty in the Torajanese culture of

A belief that all of the gods are manifestations of this supreme being. This belief is the same as the belief of smartism, which also holds that the different forms of God, Visnu, Siva are different aspects of the same Supreme Being. Lord Shiva is also worshipped in other forms such as "Batara Guru" and "Maharaja Dewa" (Mahadeva) are closely identified with the Sun in local forms of Hinduism or Kebatinan, and even in the genie lore of Muslims.

A belief in the Trimurti, consisting of:

- Brahma, the creator

- Wisnu or Visnu, the preserver

- Ciwa or Siva, the destroyer

A belief in all of the other Hindu gods and goddesses (Dewa and Bharata)

The sacred texts found in Agama Hindu Dharma are the Vesas. Only two of the Vedas reached

One of Hinduism's primary ethical concerns is the concept of ritual purity. Another important distinguishing feature, which traditionally helps maintain ritual purity, is the division of society into the traditional occupational groups, or varna (literally, color) of Hinduism: Brahmins (priests, brahmana in indonesia),Kshatriya (ruler-warriors, satriya in Indonesian), Vaishya (merchants-farmers, waisya in Indonesian), and Shudra (commoners-servants, sudra in Indonesian). Like Islam and Buddhism, Hinduism was greatly modified when adapted to Indonesian society.

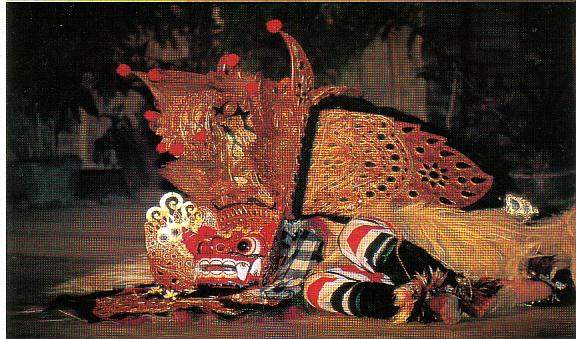

The caste system, although present in form, was never rigidly applied. The epics mahabarata (Great Battle of the Descendants of Bharata) and Ramayana (The Travels of Rama), became enduring traditions among Indonesian believers, expressed in shadow puppet (wayang) and dance performances.

The Indonesian government has recognized Hinduism as one of the country's five officially sanctioned, monotheistic religions. Partly as a result, followers of various tribal and animistic religions have identified themselves as Hindu in order to avoid harassment or pressure to convert to Islam or Christianity. Furthermore, Indonesian nationalists have laid great stress on the achievements of the Majapahit Empire – a Hindu state – which has helped attract certain Indonesians to Hinduism. These factors have led to a certain resurgence of Hinduism outside of its Balinese stronghold.

JAVANESE HINDUISM

Both Java and Sumatra were subject to considerable cultural influence from the Indian subcontinent during the first and second millennia of the comman Era. Many Hindu temples were built, including Prambanan near Yogyakarta, which has been designated a World Hertage Site; and Hindu kingdoms flourished, of which the most important was majapahit.

In the sixth and seventh centuries many maritime kingdoms arose in

Majapahit was based in

Hinduism has survived in varying degrees and forms on Java; in recent years, conversions to Hinduism have been on the rise, particularly in regions surrounding a major Hindu religious site, such as the Klaten region near the Prambanan temple. Certain ethnic groups, such as the Tenggerese and osings, are also associated with Hindu religious traditions.

HINDUISM ELSEWHERE IN THE ARCHIPELAGO

Main article:Hinduism in Sulawesi

The Bodha sect of sasak people on the

Among the non-Bali communities considered to be Hindu by the government are, for example, the Dayak adherents of the kaharingan religion in kalimantan tengah, where government statistics counted Hindus as 15.8 % of the population as of 1995. Nationally, Hindus represented only around 2 % of the population in the early 1990s.

Many manusela and nuaulu people of seram follow

Similarly, the tana toraja of sulawesi have identified their animistic religion as Hindu.

The batak of

HINDU HOLIDAYS IN

Hari Raya Galungan

Galungan Celebrates the coming of the Gods and the ancestral spirits to earth to dwell again in the homes of the descendants. The festivities are characterized by offerings, dances and new clothes.

Hari Raya Saraswati

Saraswati Balinese Hindu belief that knowledge is an essential medium to achieve the goal of life as a human being. This day celebrates Saraswati in

Saraswati Day is celebrated every 210-days on Saniscara Umanis Wuku Watugunung and marks the start of the new year according to the Balinese Pawukon calendar. Ceremonies and prayers are held at the temples in family compounds, villages and businesses from morning to

Hari Raya Nyepi

Nyepi is a Hindu Day of Silence or the Hindu New Year in the Balinese Saka calendar. The largest celebrations are held in

Nyepi (Balinese New Year) is also determined using the Balinese calendar (see below), the eve of Nyepi falling on the night of the new moon whenever it occurs around March/April each year. Therefore, the date for Nyepi changes every year, and there is not a constant number of days difference between each Nyepi as there is for such days as Galungan and Kuningan. To find out when Nyepi falls in a given year, you will need information on the cycles of the moon for that year. Whenever the new moon falls between mid-March and mid-April, that night will be the night of great activity and exorcism island-wide, while the next day will be the day of total peace and quiet, where everything stops for a day.

IN A POLITICAL CONTEXT

While many Javanese have retained aspects of their indigenous and Hindu traditions through the centuries of Islamic influence, under the banner of 'Javanist religion' (kejawen) or a non-orthodox 'Javanese Islam' (abangan, cf. Geertz 1960), no more than a few isolated communities have consistently upheld Hinduism as the primary mark of their public identity. One of these exceptions are the people of the remote Tengger highlands (Hefner 1985, 1990) in the

At the same time, the East Javanese branch of the government Hindu organization, PHDI, in an annual report claims the 'Hindu congregation' (Umat Hindu) of this province to have grown by 76,000 souls in this year alone.

However, there are problems in estimating the real number of Hindus which may be bigger. The rate of conversion accelerated dramatically during and after the collapse of former President suharto's authoritarian regime in 1998. Despite their local minority status the total number of Hindus in Java now exceeds that of Hindus in

- Official Recognition

Officially identifying their religion as Hinduism was not a legal possibility for Indonesians until 1962, when it became the fifth state-recognized religion. This recognition was initially sought by Balinese religious organizations and granted for the sake of

Religious identity became a life and death issue for many Indonesians around the same time as Hinduism gained recognition, namely in the wake of the violent anti-Communist purge of 1965-66 (Beatty 1999). Persons lacking affiliation with a state recognized-religion tended to be classed as atheists and hence as communist suspects.

Despite the inherent disadvantages of joining a national religious minority, a deep concern for the preservation of their traditional ancestor religions made Hinduism a more palatable option than Islam for several ethnic groups in the outer islands.

In the early seventies, the toraja people of sulawesi were the first to realize this opportunity by seeking shelter for their indigenous ancestor religion under the broad umbrella of 'Hinduism', followed by the Karo Batak of sumatra in 1977 (Bakker 1995).

In central and southern

Compared to their counterparts among Javanese Hindus, many dayak leaders were also more deeply concerned about Balinese efforts to standardize Hindu ritual practice nationally; fearing a decline of their own unique 'Hindu Kaharingan' traditions and renewed external domination.

By contrast, most Javanese were slow to consider Hinduism at the time, lacking a distinct organization along ethnic lines and fearing retribution from locally powerful Islamic organizations like the Nahdatul Ulama (NU). The youth wing of the NU had been active in the persecution not only of communists but of 'Javanist' or 'anti-Islamic' elements within Sukarno's Indonesian Nationalist Party (PNI) during the early phase of the killings (Hefner 1987). Practitioners of 'Javanist' mystical traditions thus felt compelled to declare themselves Muslims out of a growing concern for their safety.

The initial assessment of having to abandon 'Javanist' traditions in order to survive in an imminent Islamic state proved incorrect. President Sukarno's eventual successor, Suharto, adopted a distinctly nonsectarian approach in his so-called 'new order' (orde baru) regime. Old fears resurfaced, however, with Suharto's 'Islamic turn' in the 1990s. Initially a resolute defender of Javanist values, Suharto began to make overtures to Islam at that time, in response to wavering public and military support for his government.

A powerful signal was his authorization and personal support of the new 'Association of Indonesian Muslim Intellectuals' (ICMI), an organization whose members openly promoted the Islamization of Indonesian state and society (Hefner 1997). Concerns grew as ICMI became the dominant civilian faction in the national bureaucracy, and initiated massive programs of Islamic education and mosque-building through the Ministry of Religion (departemen agama), once again targeting Javanist strongholds. Around the same time, there were a series of mob killings by Muslim extremists of people they suspected to have been practicing traditional Javanese methods of healing by magical means.

In terms of their political affiliation, many contemporary Javanists and recent converts to Hinduism had been members of the old PNI, and have now joined the new nationalist party of Megawati Sukarnoputri. Informants from among this group portrayed their return to the 'religion of Majapahit' (Hinduism) as a matter of nationalist pride, and displayed a new sense political self-confidence.

Political trends aside, however, the choice between Islam and Hinduism is often a highly personal matter. Many converts reported that other members of their families have remained 'Muslims', out of conviction or in the hope that they will be free to maintain their Javanist traditions in one way or another.

IN A SOCIAL CONTEXT

A common feature among new Hindu communities in Java is that they tend to rally around recently built temples (pura) or around archaeological temple sites (candi) which are being reclaimed as places of Hindu worship.

One of several new Hindu temples in eastern Java is Pura Mandaragiri Sumeru Agung, located on the slope of Mt Sumeru, Java's highest mountain. When the temple was completed in July 1992, with the generous aid of wealthy donors from bali, only a few local families formally confessed to Hinduism. A pilot study in December 1999 revealed that the local Hindu community now has grown to more than 5000 households.

Similar mass conversions have occurred in the region around Pura Agung Blambangan, another new temple, built on a site with minor archaeological remnants attributed to the

A further important site is Pura Loka Moksa Jayabaya (in the

A further Hindu movement in the earliest stages of development was observed in the vicinity of the newly completed Pura Pucak Raung (in the Eastern Javanese district of Glenmore), which is mentioned in Balinese literature as the place where the Hindu saint Maharishi Markandeya gathered followers for an expedition to Bali, whereby he is said to have brought Hinduism to the island in the fifth century AD.

An example of resurgence around major archaeological remains of ancient Hindu temple sites was observed in Trowulan near Mojokerto. The site may be the location of the capital of the legendary Hindu empire Majapahit . A local Hindu movement is struggling to gain control of a newly excavated temple building which they wish to see restored as a site of active Hindu worship. The temple is to be dedicated to Gajah Mada, the man attributed with transforming the small hindu

A new temple is being built East of Solo (Surakarta) It is a Hindu temple that has miniatures of 50 sacred sites around the world. It is also an active kundalini yoga meditation centre teaching the sacred javanese tradition of sun and water meditation. There are many westerners as well as javanese joining in.

Although there has been a more pronounced history of resistance to Islamization in

IN AN ECONOMIC CONTEXT

Taking Pura Sumeru as an example, it is also important to note that major Hindu temples can bring a new prosperity to local populations. Apart from employment in the building, expansion, and repair of the temple itself, a steady stream of Balinese pilgrims to this now nationally recognized temple has led to the growth of a sizeable service industry. Ready-made offerings, accommodation, and meals are provided in an ever-lengthening row of shops and hotels along the main road leading to Pura Sumeru. At times of major ritual activity tens of thousands of visitors arrive each day. Pilgrims' often generous cash donations to the temple also find their way into the local economy.

Pondering with some envy on the secret to the economic success of their Balinese neighbors, several local informants concluded that "Hindu culture may be more conducive to the development of an international tourism industry than is Islam. Economic considerations also come into play insofar as members of this and other Hindu revival movements tend to cooperate in a variety of other ways, including private business ventures which are unrelated to their joint religious practices as such.